Pelagius, Augustine, and Arminius

The Reformed Church of the Netherlands (RCN) has been the official denomination of the Republics of the United Provinces of the Netherlands since 1571. On the occasion of the Synod of Endem, they established the Belgian Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism (for the Dutch-speaking provinces) or the Catechism of Geneva (for French-speaking provinces) as the confessional documents and indispensable requirements for the ordination of their ministers. After the Abjuration Act in 1581, Catholic churches were purified by removing images and symbols that were then confiscated as property of the RCN. Other non-Calvinist Protestant groups were tolerated but with austere conditions and limitations on their freedom of worship and religion. Since RCN is a Protestant and, above all, Calvinist denomination, the motif “justification by grace through faith” was vital. For this reason, any proximity to the appearance of works-righteousness was viewed negatively and accused of adhering to the heresy of Pelagianism.

James Arminius (1560-1609) was pastor of the Reformed Church in Holland (between 1588 and 1603) and professor of theology at the University of Leiden (between 1603 and 1609). He lived in the heyday of the Eighty Years' War (1568-1648), losing his mother and brothers in the Oudewater massacre of 1575. Among the tragedies of life, an abundance of God's grace illuminated his youth so that he was not forsaken. A Catholic, Theodore Emilio (? - 1574), took care of his basic education and gave opportunities for Arminius to discover his calling. It was in this university environment that the young academic realized his intellectual capacity. With the support of the Amsterdam's classis (church governing body), he pursued his academic studies on the condition that he would return the scholarship by pastoring. His ordination took place in 1588.

Thus far in his life, many challenges had been overcome, but many more would yet come. The following challenges revolved around a doctrinal tripod of human beings, sin, and salvation. Based on his perspectives on anthropology, hamartiology, and soteriology, Arminius was accused of being Pelagian or semi-Pelagian. However, this is a mistake—Arminius’ articulation of human salvation was clearly not Pelagian.1

Pelagius (350-423) was a British monk who denied "Original Sin," believing that human nature was neutral and that people learned to sin through socialization. The only action of God's grace for Pelagius was the communication of His law to people's hearts, a kind of natural and general revelation common to all people of the human race. Since humanity was aware of these precepts, then it would be up to individuals to follow each commandment. Pelagius taught that each human being was completely responsible for his/her own salvation, without any external intervention nor any operation of grace. The Pelagian theology, therefore, taught that the image of God in humankind was neither lost nor corrupted, but it was intact, because Adam's sin affected only himself and not his posterity. Further, it taught that free will was also intact, and it is this agent that at the same time blames and empowers human beings to be saved and to live in absolute perfection.2

It is clear that Pelagius' position is not grounded in Scripture nor experience. For this reason, Augustine (354-430) undertook a major attack on his doctrines, denouncing errors and their logical consequences.3 Augustine said, unlike Pelagius, that Adam's sin brought serious consequences for himself and his descendants. The first of these was linked to the imago Dei, because the warning that disobedience to the divine command would bring "death" included both a spiritual and a physical death. Spiritually, Adam died in relational terms with God; he lost the ability to seek the Creator, becoming alienated, dead in his crime and sin. Physically, Adam’s days were numbered, his longevity was counting down, and neither he nor any of his descendants would be physically immortal. As a result, the image of God was corrupted in its entirety. Any descendant of Adam was born already spiritually "dead." This fall extended to all beings collectively so that "there is no one righteous, not even one; there is no one who understands, there is no one who seeks God" (Romans 3:10-11). Because free will had been lost with the fall of Adam, salvation occurs not by human action but by divine action. God is the one who begins, continues, and ends the salvation of people.

Augustine called all these effects of the fall “Original Sin.”

For Arminius, the image of God was not lost but completely corrupted. This is in line with Augustinian thinking, with Calvin's ideas, and with the RCN's confessional documents at that time (Belgian Confession and Heidelberg Catechism).4 Arminius articulated two dimensions of the Image of God—one called essential and the other accidental.5 The essential image contains the natural free will, which, despite not having been lost, has been corrupted in the human being so that decisions are not the wisest nor the most correct. The accidental image, however, concerns spiritual free will, something that was lost with the fall of Adam.6

Arminius was very emphatic about what has happened to spiritual free will since the fall of Adam. According to him, “about grace and free will, this is what I teach, about Scripture and orthodox consensus: the free will is unable to initiate or perfect any true and spiritual good without grace.”7 He also said that “in that [fallen] state, man's free will for what is good is not only hurt, crippled, sick, distorted and weakened; it is also imprisoned, destroyed and lost.”8 Arminius agreed with the Augustinian proposal that the unregenerate human being is "dead" and is therefore spiritually incapable.9 The solution to this, then, must come from outside the individual. It must come from God.10 Based on this, Arminius distanced himself from Pelagianism.11

Arminius also distanced himself from the church in Holland on its understanding of salvation.

Arminius and his contemporaries understood grace to be the way in which the will is made free. They disagreed, however, on human response.

The Calvinism that Arminius disagreed with taught that the whole experience of salvation for the elect, from preventing to sanctifying grace, did not encompass a human response. Arminius agreed that it was only because of the grace of God that the human will was made free but that this took place through an enabling grace that allowed humans to respond to God in faith.

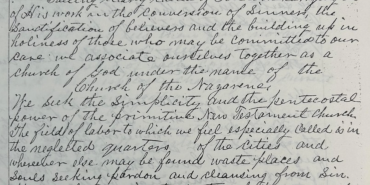

Arminius’ contributions were very important for European evangelicalism in the 18th century. Although many of his ideas were not entirely new, they influenced important movements such as Wesleyan Methodism (18th century) and the Holiness Movement (19th century). The Church of the Nazarene is indebted to his legacy.

Vinicius Couto is an ordained elder leading the ministry of First Church of the Nazarene of Vinhedo, São Paulo. He is also a professor at the Nazarene theological seminary in Brazil.

1. For Arminius' biographical information, see: Nathan Bangs, The Life of James Arminius, D.D., Formerly Professor of Divinity in the University of Leyden. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1843; and John Guthrie, The Life of James Arminius. Nashville: E. Stevenson & FA Owen, 1857. See also: Carl Bangs, Arminius: A Study in the Dutch Reformation. Eugene: Wipf and Stock Publishers, 1985. For his works, see James Arminius, The Works of James Arminius, 3 vols. Auburn and Buffalo: Derby, Miller and Orton, 1853; and James Arminius, The Missing Public Disputations of Jacobus Arminius: Introduction, Text, and Notes, Ed. Keigh Stanglin, Boston: Brill, 2010.

2. For more information on Pelagius’ ideas, see B. R. Rees, Pelagius: Life and Letters. Rochester: Boydell & Brewer Ltd, 1998.

3. Augustine’s main works dealing with Pelagius are: Against Two Letters of the Pelagians; On the Grace of Christ, and on Original Sin; On Merit and the Forgiveness of Sins; and On the Proceedings of Pelagius.

4. After the Synod of Dort (1618-19), the canons of Dort were added as the confessional tripod of the RCN, called “forms of unity.”

5. James Arminius, The Works of James Arminius, vol. 1 (Auburn and Buffalo: Derby, Miller and Orton, 1853), 123-125; James Arminius, The Missing Public Disputations of Jacobus Arminius: Introduction, Text, and Notes, Ed. Keigh Stanglin, (Boston: Brill, 2010), 219-232.

6. John Wesley thought in the same terms as Arminius with regard to the essential and the accidental image. However, he added the idea of political image (based on Isaac Waats), giving the imago Dei a three-dimensional character.

7. Arminius, The Works of James Arminius, vol. 1, 473.

8. Ibid.

9. Arminius, The Missing Public Disputations of Jacobus Arminius: Introduction, Text, and Notes, Ed. Keigh Stanglin, (Boston: Brill, 2010), 213-216.

10. Arminius, The Works of James Arminius, vol. 1, 231.

11. He even explicitly called Pelagianism “heretical” (Arminius, The Works of James Arminius, vol. 1, p. 235. For more explicit criticism of Pelagius’ doctrines by Arminius, see p. 198, 201-2, 275, 290, 294-5, 299, 332-6, 348; see also Arminius, The Missing Public Disputations of Jacobus Arminius, 281-296, 333-346, 406; Arminius, The Works of James Arminius, vol. 3, 281, 342, 354, 484).

Holiness Today, November/December 2020

Please note: This article was originally published in 2020. All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at that time but may have since changed.