Identity: The Self and the Savior

Much contemporary writing and thinking focuses on “the self.” We are encouraged to express ourselves, to find our authentic selves, to develop self-worth and a good self-image. For some decades now, that has been seen as particularly important in bringing up children. In place of the old legalism with its strict rules and discipline and the threat of punishment for stepping out of line, children are to be affirmed positively and encouraged. Dr. Spock rules.[1]

But the “positive” attitude also became part of the wider culture. Norman Vincent Peale published The Power of Positive Thinking in 1952. That great philosopher, Bing Crosby, also taught us to “accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative and latch on to the affirmative.”[2] That is the way to a healthy sense of identity and self-worth.

Over against that, much traditional Christian preaching seemed out of touch. The Christian summons to self-denial seemed negative and even destructive. If following Christ means denying myself and taking up my cross, is this not psychologically damaging?

During this cultural paradigm shift, some of the old hymns came in for criticism. Isaac Watts’ question, “Would he devote that sacred head for such a worm as I?” (From “Alas! and Did My Savior Bleed”) is seen as “worm theology”! It is needless self-harm. It is self-denigration. The harping on about guilt and judgment and the focus on judgment and punishment has to be rejected. In particular, such Christian preaching is seen to be damaging to the marginalized and the oppressed and those with low self-esteem. Marxists, abolitionists and feminists have rightly pointed out that the Christian call to self-denial has too often been wrongly used to suppress workers, slaves, and women.

What shall we do, then, with the Christian call to self-denial? After all, it was Jesus Himself who said, “If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me” (Mark 8:34, NRSV). Of course, that was not all that Jesus said. He also said, “Come to me, all you that are weary and are carrying heavy burdens, and I will give you rest” (Matthew 11:28, NRSV).

Is there a paradox here?

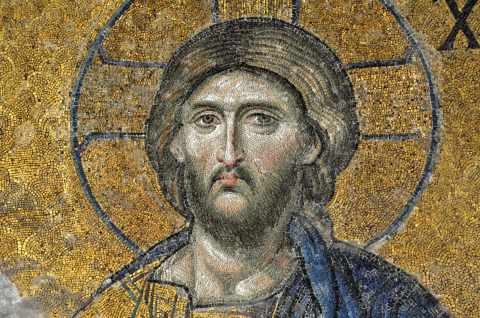

Perhaps there is a mystery here. Perhaps the Christian faith is to be seen as the supreme paradox – the paradox of the cross and the resurrection. Could it be that the old emphasis on law and judgment was part of a profound wrestling with the mystery of the cross, and the preaching of “Christ crucified”? To be centered on “Christ crucified” as Paul wrote (see 1 Corinthians 1:23) cannot be wrong!

But perhaps this emphasis can be unbalanced if it is not complemented by an equal stress on resurrection. After all, when Paul summarized the gospel he had preached to the Corinthians, it was not only “that Christ died for our sins according to the Scriptures,” but also, “that he was raised on the third day according to the scriptures” (1 Corinthians 15:3-4, NRSV).

Should we then think of the Christian gospel as inherently paradoxical? It is the crucified one who is raised immortal. It is the one under judgment who is declared the righteous one. And that pattern of dying and rising which is the shape of the gospel also characterizes the life and experience of the Christian. Yes, I must deny myself, die with Christ, lose my life. But the cross was not Jesus’ final destiny. It was the way to glory. And so for the Christian, the purpose of self-denial is to find his or her true self, true worth, and true identity in Christ.

A Wider Dimension

There is a wider dimension here. The popularity of the word “self” in contemporary discourse is part of the whole focus of modernity on the individual. Our whole culture has encouraged us to think about the life of the individual, the rights of the individual, individual choice, individual identity. We think of a “person” as an individual, a self-conscious “self” to protect, nurture, and develop.

But the irony is that individuals are then classified into collectives – the middle class, the workers, consumers, those who are said to have certain “sexual preferences,” generation Z, and so on. People are reduced to statistics and commerce shapes our preferences by using algorithms on the internet.

The way we Christians think of ourselves has also been influenced by the individualism of modernity. The true and valid summons to personal faith in the Lord “who loved me and gave himself for me” (Galatians 2:20) has been twisted into individualistic religion. We were taught to sing, “On the Jericho road, there’s room for just two.” The life of faith became just a matter of “Jesus and me.”

In fact, the word often translated in modern versions of the Bible as “self” is the word anthropos which does not mean “self,” but “humanity.” In the Hebrew thinking that underlies the New Testament, the idea is not an individualistic, nor a collective, but a corporate concept. As anthropos then, my human nature is not an individualistic reality but the common human nature that I share with all humankind. I inherited it from my parents within the Creator’s provision of the family – father, mother, and children. As a new-born infant, my identity – who I am – was shaped by relationships within the family.

All this means that if we are to think biblically, we must see that we are not isolated “selves,” individuals who pursue our lonely path through life trying to create our own “identity” or even our own individualistic salvation. Our identity is not shaped primarily by the collective to which we are assigned by class, generation, or anything else. Our identity is formed by our relationships within the family. And yet, of course, that is still a sinful identity, for there is no family – not even the most sophisticated and devoted – which is not part of corporately sinful humanity.

That is why redemption means to be re-formed and re-shaped within the family of God, the Church, the body of Christ. For there, our joyful, affirming fellowship is not just with each other, but is “the fellowship of the Holy Spirit” so that “our fellowship is with the Father and with his Son Jesus Christ” (2 Corinthians 13:13 and 1 John 1:3, NRSV).

It is within that Trinitarian context, loved and cherished, that we learn to deny ourselves and to say as Paul says in so many different ways, “Not I, but Christ.”[3]

T. A. Noble is research professor of theology at Nazarene Theological Seminary, Kansas City, and senior research fellow in theology at Nazarene Theological College, Manchester.