Transformation Through Worship

“Worship: Why bother? My relationship with God is private—it’s between me and God.”

“My best times of worship are in my car or on the hiking trail.”

“Oh, we stopped going to that church; we weren’t getting anything out of the worship.”

“When they sing those kinds of songs, I just can’t worship.”

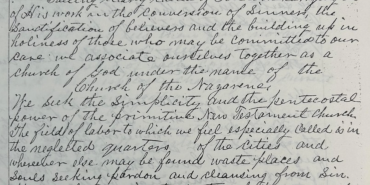

Statements like these reveal our confusion about worship—what it is, what it does, and who it is for. I grew up in the Church of the Nazarene in a day when most every Nazarene church sang out of the Worship in Song (1972) hymnal. You could visit a dozen Nazarene churches and the worship services would look, sound, and often smell (hymn books have a certain smell, you know) similar: welcome and prayer, a few hymns and a chorus, offering, sermon, altar call. Since that time, our worship has grown more diverse—especially when considered in a global context.

Some churches still sing out of the hymnal, while a growing number embrace the latest contemporary worship music from the broader evangelical marketplace. Some have moved toward more frequent celebration of the sacrament of communion in weekly worship. Some evoke a sense of the sacred through digital projection, lighting, and other visual arts—a kind of modern-day stained glass. We can (and do) still have unity in essentials amidst this diversity, but these differences do make a difference.

As I enter my third decade leading people in worship, the state of worship in our churches today is of deep importance to me. I’ve developed a few core convictions about worship that I believe can help us understand why we do what we do in worship and the impact it has on our spiritual lives.

We were created to worship

James K. A. Smith, in Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview and Cultural Formation, defines man as homo liturgicus—we are “liturgical animals” who simply cannot not worship. This is not necessarily a new insight. Famously, Augustine begins Book 1 of his Confessions by proclaiming, “Great are You, O Lord, and greatly to be praised. . . . And man, being a part of Your creation, desires to praise You. . . . You move us to delight in praising You; for You have formed us for Yourself, and our hearts are restless till they find rest in You.” Similarly, the first question and answer of the Westminster Shorter Catechism reminds us that humanity’s purpose is “to glorify God and enjoy Him forever.” Yes, we were created to worship.

Northwest Nazarene University professor Brent Peterson emphasizes this truth by making it the title of his book, Created to Worship: God’s Invitation to Become Fully Human.

We receive our authentic humanity when we fulfill our purpose in the communal worship of Almighty God.

As liturgical animals, our natural tendency as human creatures is to devise rituals and practices that organize and help us make sense of our lives. These practices reflect our desires, the orientation of our “loves”—and that which we love, we worship.

Worship is corporate before it is personal

This is not a statement about importance but about primacy or priority—about “which comes first.” In short, there was always a church, a worshipping community called together by God, well before you and I came along. Christians aren’t created ex nihilo (“out of nothing”), and we aren’t a bunch of autonomous individuals on our own little journeys of self-discovery and spiritual enlightenment.

The God who is a communion of Three Persons created us in the divine image, and this God works redemptively through the created order—through matter, through nature, through people with bodies, through the Body of Christ called church. In a very real way, I don’t know how to pray, how to worship, or how to read the Bible apart from faithful Christ-followers who have gone before me—parents and Sunday school teachers, preachers and youth pastors, poets and theologians like Charles and John Wesley, and so on, back through an unbroken thread in the tapestry of apostolic faith.

Now, by no means do I want to denigrate personal worship. A Christian life punctuated only by corporate worship on Sundays but never engaged in personal worship is anemic and unhealthy. Personal worship Monday through Saturday is vital, but corporate worship is far more than just the “overflow” or the “icing on the cake” of the Christian life.

Instead, think of corporate worship more like the cake pan that forms and gives shape and structure to the Christian life. Without it, we’d be a mess.

By the way, it’s not “private worship" — worship is personal, but it’s never private. Even if no one else is physically present, when I worship, I’m joining my voice with “the whole company of heaven,” in the words of one communion ritual, “singing the hymn of your unending glory.”

Worship is the work of the people

Before it took on specifically religious meaning, the word liturgy had to do with a whole range of public acts or services to the community. So in this sense, it’s appropriate that we call it a church service—as long as we bear in mind that what we’re offering is a service to God, and not, first and foremost, to those who showed up for the service. If we get something out of the service, too, well then thanks be to God—but it doesn’t exist for us.

Thinking of worship as the work of the people emphasizes the public and communal nature of worship. The church is a body—the Body of Christ. We call it “corporate” worship, after all, because it’s the worship of the corpus, the Body.

It’s not the work of the pastor or priest, and certainly not the work of the worship leader and music team.

It’s the work of the entire congregation, offering up their praises and their selves as a living sacrifice to God. The congregation isn’t the “audience” (please never use that term to describe your Sunday morning “crowd”).

Rather, the congregation (collectively) is the performer (singular), performing as one for an audience of (Three-in-)One.

We become what we worship

If we worship that which we supremely love, then eventually we begin to take on the character and values of the object of our worship. We know this from ordinary life, don’t we?

Have you ever noticed how the more time you spend with people you truly love and admire, the more you begin to mimic and adopt their mannerisms, patterns of speech, maybe even aspects of their personality?

For better or worse, you grow alike as you grow together.

In a similar way, if we love our jobs, our money, and our “stuff,” our imagination begins to be consumed with accumulation and preservation of wealth.

We slowly buy into what Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann calls the “myth of scarcity,”1 and our concern becomes mainly for “us and ours.” We develop vices that the world calls virtues, like pride and greed (which are “deadly sins,” actually), and wink at our sin with jokes about “workaholism.” We grow to see ourselves in terms of production and consumption, rather than creatures who depend upon a loving Creator for our provision. The first sin, and the root of all sin, is idolatry: putting something other than God in God’s rightful place. (See Genesis 3 and Exodus 20:1-6).

If we cannot not worship, then our worship of anything other than the one true God who raised Jesus Christ from the dead means we are guilty of idolatry. By orienting our desires toward the God who was in Christ, and following Christ’s example of obedience to the Father, we offer our worship toward the only One who is worthy to receive it.

Doxology, after all, is not just giving glory (doxa) to God, but also with recognizing and responding to the glory of God—seeing God aright, for who God really is, and offering up due praise and adoration. In so doing, the Holy Spirit makes us more and more into the likeness of Christ, restoring the Imago Dei, the image of God within us.

As Brother Lawrence puts it in The Practice of the Presence of God, “We must know before we can love. In order to know God, we must often think of Him. And when we come to love Him, we shall then also think of Him often, for our heart will be with our treasure.”2

The shape of worship shapes us

The rituals and liturgies (religious or secular) that fill our lives ultimately form our imaginations (our vision of the good life) and instill within us a certain identity (who we believe ourselves to be). In other words, worship is formational.

In Desiring the Kingdom, Smith reminds us that “there are no neutral practices.” The practices that we are immersed in are “intentionally loaded to form us into certain kinds of people—to unwittingly make us disciples of rival kings and patriotic citizens of rival kingdoms.”3 The most powerful of these practices—what Smith calls “secular liturgies,” seek to form us into good consumers, for instance, or good citizens, or “fans.” Alternatively, the liturgies of the Christian faith are oriented toward forming us into faithful Christians.

Thus, worship is also trans-formational. Its goal is to send us out different than we came in.

The fancy Latin phrase the church has used to describe this process is "lex orandi, lex credendi, lex vivendi." In plain language, the way (or law) of prayer is the way of believing, which is the way of living. Or perhaps we might say, right worship is the way to right belief and a good life. And the converse is true as well: worshiping poorly leads to wrong beliefs and a lousy life. The traditional “four-fold” shape of Christian worship involves:

- Gathering, in Christ’s name, in the presence of God, in the power of the Holy Spirit;

- The Word—receiving Christ through Christian proclamation

- The Table—receiving Christ through the sacrament of communion

- Being sent, or dismissed, to be Christ’s Body in the world, having been fed by His Word and the symbols of the Word made flesh-and-blood.

Just think about how powerfully and deeply that “shape” shapes us, if we will allow it to, not only at the intellectual level but at the level of our bodies. We are invited into a divine rhythm of being called together for worship; filled up with and formed into the Body of Christ; and sent back out into the world as Christ; only to come back together seven days later on Sunday, the day of resurrection (and the first day of creation), to begin again. In a very real sense, this is how Christians are made, and made new.

Brannon Hancock is assistant professor of practical theology at Wesley Seminary at Indiana Wesleyan University and worship pastor at Marion, Indiana, First Church of the Nazarene.

Holiness Today, Mar/Apr 2016

Please note: This article was originally published in 2016. All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at that time but may have since changed.