Educating the Laity: The Crucial Need for Discipleship

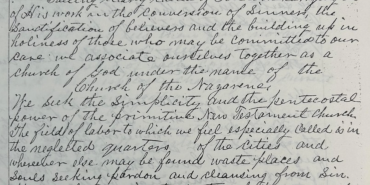

Discipleship is necessary to maintain a biblically, theologically, educated laity in the Church of the Nazarene. The term “laity” implies something overlooked in our language: all Christians comprise the laos or the people of God.

While this term is used to distinguish ministers (the clergy) from participants in the church (the laity), the fact is any ambivalence toward educating the laity reveals an equal ambivalence toward the discipleship of all Christians. As ministers, we must accept our mandate to disciple everyone, because the people of God need discipling to be the body of Christ. Failure here lets down the entire body of Christ, not just the laity.

Discipleship, the deliberate following of Jesus through study and action, serves as one of the key pillars of the church.

Discipleship is not everything the church practices. Churches engage in witness and mission, exercise stewardship, express and are shaped by worship, live in service and fellowship . . . and they disciple. Collectively these elements provide the ecology of the life of the church. Each has its place. Yet, we need discipleship to help embrace the full meaning of the church’s existence. When people forget one of the basic reasons for the church’s existence, they soon lose motivation and become subject to manipulation.

Historically the church has recognized this important task, discipling the laity, at key historic junctures. The passion for education surfaces from the pain of the Jewish diaspora, where love of God and devotion to Torah elevated discipleship to an expression of prayer and worship. Love for God could never be separated from learning knowledge of God if that love was to have substance and meaning.

Christians inherited this view and should recognize that the search for education is as much an expression of devotion as it is an attempt to command facts and information. We seek to know as we are known by God. The Jewish people had come to realize that neither the power of the nation or the sanctity of the Temple would keep them from their own self-destructive tendencies. Only the knowledge of God would preserve their way as the people of God; neither strategy nor alliances would work otherwise.

The Early Church definitely embraced education as the key point not only in the initiation of new Christians into the life of the church but also in the deepening of Christian conviction. What we now know as historic doctrinal formulations and scripture served as resource for the instruction (catechesis) of potential believers and ongoing members. All of the early church fathers were passionately involved in education (Augustine saw this as one of his central duties each year), and the church needed a laity that knew the faith since they often lived in a deeply pluralistic and divided world. The Early Church did not even know “how” to separate evangelism and education, witness and discipleship, since a literate laity was required to survive.

Yet, even by Augustine’s day, the loss of discipleship was already growing due to the rise of Constantine and the creation of a “civil religion” anchored in Christian language and identification. When people “joined” the church rather than “became” disciples, soon civil religion infected laity and clergy alike. Early in the history of the church we discovered that to forsake educating the laity was to risk becoming a cultural institution rather than a convicted community.

When the church fails to educate its laity, it soon becomes captive to the political and cultural forces in the world and soon finds itself a handmaiden to the dominant culture rather than a church of dedicated, passionate, informed “people” of God. When civil religion could no longer sustain either churches or their civilization, it took laity in the form of monastics (many early monastics were laity rather than priests) to regain something of role of church teacher and to partner with religious orders to retain the faith by preserving its teachings and living its faith through what we know as the “dark ages.”

The Reformation revolved as much around the need for a literate laity as any other historical factor. Not only did Rome fail in responding to the Reformers but it failed initially because it did not seek to prepare a laity that could withstand the excesses and manipulation of the indulgence system. Part of the problem of the lack of a literate laity (the poverty and feudal systems of the medieval world reveal) is that people who engage the church lack the resources to discern the faith and thus become manipulated by religious imposters.

As much as Rome was guilty of creating a penitential system, it was even guiltier of de-emphasizing teaching and critical thought to the point its congregants and priests could not recognize their own errors. Luther’s renewal/reformation was as much a battle to educate people to the faith as it was a strategy to destroy indulgences. Luther knew the importance of a literate laity to the point he translated the Bible into the German language, wrote and published sermons, wrote catechisms, created family resources, pressed for universal education of boys and girls, and exchanged the vestments of the priest for the robes of the teacher.

When you want renewal in the church you have to educate the “people” of God. Rome failed to do so and fell victim to its own errors. The Reformers (Luther, Calvin, even Zwingli and the Anabaptists) vowed not to make this mistake less the church fall not to cultural forces without but to manipulation from within.

Perhaps it is our own heritage in John Wesley where we encounter the need of an educated laity to preserve a movement of God. There is no doubt John’s ministry was part of a powerful Evangelical renewal across the United States and England. Thousands responded to Wesley, Whitfield, even Jonathan Edwards, in the U. S. What distinguishes Wesley, particularly as a movement that evangelized and renewed the church, was his dedication to education as a part of his evangelistic renewal.

There is ample evidence, thanks to the work of Tom Albin and others, that much of the evangelistic thrust was not only conserved through the Methodist classes and bands, but it was actually created in those small groups. Albin’s review of Methodist diaries reveals that often people went through spiritual transformations “in” the class meetings and those experiences were sealed in the learning and accountability that followed. Whitfield’s famous dictum that his evangelistic thrust yielded “rope of sand” while John Wesley’s created a movement rests as a testimony to educating as well as evangelizing the laity.

This pithy observation could be played out over a number of “evangelistic” strategies that followed this first Evangelical revival. How many times have we seen movements that yielded massive initial commitments, only to see those souls drift away like the sands of time when education is not an equal partner in the evangelistic effort?

We need to educate the “laity,” the people of God, or ultimately we will fail as stewards of the very lives God has provided us.

It should be noted that Methodism relied on this educated laity as part of what David Hempton calls “The Empire of the Spirit.” Often lay Methodists, carried globally along with the British Empire, brought the Methodist message with them.

Circuit riding preachers that followed after the American expansion to the west also relied on lay helpers to sustain preaching charges along the circuit.

In places like Britain, where the second generation of Methodists abandoned education and accountability for experience alone, the movement actually fell victim to cultural forces. This localized example of Constantinianism (like the early church) escalated to the point that Methodist historians note, for a season, British Methodism was reduced to a political movement instead of a vital church.

However, where literate laity emerged to partner with clergy around the globe, Methodism became the fastest growing movement of the modern era.

Literate laity not only conserve evangelistic outreach, they sustain it over time insuring the stewardship of God’s work for generations.

Stewardship might be the last historical theme. The rise of the British and North American Sunday School movement might be seen as an attempt to steward resources to insure an educated laity. Much is made of the movement as an evangelistic effort, often entering cities before pastors from denominations. However, the Sunday school movement was also concerned with the stewardship of resources so that the maximum number of laity could be educated without redundant efforts or costs.

In an era of curriculum glut and consumer choice we miss the most important aspect of the original Sunday School “Union”/convention movement. Many of the early Sunday School movements were regional, localized ministries with homegrown materials often respecting local contexts but lacking staying power over time. The early movement experienced redundancies in resources, revealed the limitations of the experiences of local educators, and often resulted in local but fragmented efforts.

What saved this movement was the creation of “unions” and “conventions” that stewarded regional efforts, cross-pollinated ideas, raised the visibility of educating the people of God as its sole priority, and sparked a movement. Unfortunately, regionalization and sectarian fragmentation later threatened the movement once more as specific agencies and alliances sought undercut collective efforts to provide discipleship to generations of believers of all ages. Sunday Schools thrived in collaborative efforts and struggled when fragmentation challenged both resources and mission.

Ori Baufman and Rod A. Beckstrom, authors of The Starfish and Spider: The Unstoppable Power of Leaderless Organizations, note that often decentralized organizations are far more adaptable to specific issues and local needs than previous “command and control” leadership strategies. However, even Baufman and Beckstrom note that “leaderless” organizations are not extremely efficient and susceptible to domestication if not maintained. Instead, they argue for a “hybrid” that involves leaders who serve as catalysts within the organization, champions for the organization, and stewards to insure resources are not replicated unnecessarily, nor efforts lost due to shifting regional contingencies.

The rise of the Sunday School Union reminds us that local efforts to educate laity, by laity, often require the right “mix” of local and global partnerships to insure faithful shepherding of efforts and strategic placement of resources where needed.

Such a partnership needs leaders passionate and focused to insure a long term commitment to a literate laity.

Discipleship must always be about the people of God. An informed laity sustains movements, resists temptations both outside the church and within, reforms, renews, and transforms the people of God into a force for the kingdom of God. Discipleship requires vigilance, stewardship, passion, and wisdom to coordinate (not command) and resource laity in their journey. If we learn from the broad strokes of the history of discipleship, we will commit to a well-educated laity, a discipled people of God.

Dean G. Blevins

Please note: All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at the time of original publication but may have since changed.