Listen. Think. Disagree?

I dislike conflict.

No, that is not strong enough. I greatly dislike conflict.

I have always been this way. My mother tells the story of me, as a young child, trying to calm down my friends when they would argue. I would go along with something I did not want to do, just so there would not be an argument.

These days, I will leave the room when politics are discussed. Even if I have a strong opinion, to me it is not worth the fight. If I post something on Facebook or Twitter, and the result is a heated debate, I will delete the entire conversation.

This is not always a good thing.

As a pastor, I recognize the need for creating an environment where differences of opinion can be shared. Hard conversations are necessary if we are going to live together in authentic community. One of the altogether appropriate critiques of the church is that we simply do not know how to talk about difficult subjects.

We have to talk about difficult subjects. And we need to learn how to disagree.

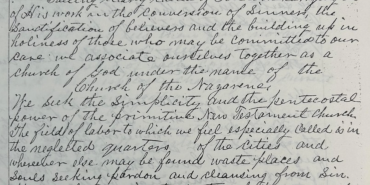

I occasionally participate in an online discussion group that attempts to provide an environment for members and friends of the Church of the Nazarene to discuss challenging issues. Everyone who joins the conversation is initially surprised when they realize that their opinion is not shared by everyone in the group. Some even come right out and say, “I thought all of you were Nazarenes. How can you disagree with me on this?”

In a TED talk viewed nearly 3 million times, writer Kathryn Schulz talks about being wrong. She explains that most of the time we are personally invested in proving that we are always right. To do this, we must be able to explain all of the people who disagree with us. She says that we go through three stages of explanation:

One, if you disagree with me, you are ignorant of the facts.

Two, if you disagree with me, even after I have explained to you all the facts, then you must be idiots.

Three, if you still disagree with me, even after you have all the facts, and I can see that you are not an idiot, then you must be evil.

You can see that this describes much of what passes for political discourse.

Unfortunately, this also happens in families. And in the church. I’ve seen it in church board meetings. Good folks found themselves on different sides of a difficult issue. One day they were worshiping together, praying together, going on missions trips together, and just a few weeks later they were challenging each other’s integrity and refusing to be in the same room.

As someone who hates conflict, this tore me up—and it also threatened to tear up our church.

While I am sure that while you are reading this you have thought of several ways to avoid such difficulties, I will state the obvious:

• We really need to listen.

Truthfully, there is no need to listen if we are absolutely confident that we are right, and if we don’t care about the relationship. As Schulz says in another portion of her TED talk, we have been culturally conditioned to strive to always be right, because only ignorant dullards (the folks who got all the red marks on their papers in school) are wrong. Of course, we know that we are sometimes wrong.

There also is no need to listen if we don’t care about the relationship. But as Christians, we really do care about each other. Learning to listen to one another is the key. As a pastor, I am trying to reconfigure our board meetings—in the past quite similar to business committee meetings—in such a way that hearing each other’s perspective and taking time to listen is a priority.

• We really need to think.

When we respond emotionally to conflict, it is likely to result in a reaction that is at best defensive—not open to listening and growing, and at worst offensive—attacking those with whom we disagree. Yet our emotions are the result of our thinking, as we interpret our experiences and the actions of others. When we think, or more specifically, when we are open to rethinking our interpretations and ideas, we are more likely to listen and consider the perspectives of others. Admittedly, the willingness to open up our personal interpretations to being challenged and changed is threatening.

Some consider vulnerability to be at the heart of personal growth and authenticity. Put another way, when we make the conscious decision not only to critically consider the ideas of others, but invite them to critically consider our ideas, we create an environment of growth and learning for everyone.

• We really need to disagree.

Les and Leslie Parrott, in their best-selling books on marriage based upon the research they have done at the Center for Relationship Development at Seattle Pacific University, state what all married couples know to be true: a healthy marriage is not based upon lack of conflict, but about knowing how to healthily resolve conflicts when they inevitably occur.

It must become a priority in our churches for leaders to create an environment where we learn to disagree without breaking relationship. This is essential if we are to creatively and authentically discuss the hard questions the younger generation is demanding we address.

Disagreements among followers of Christ is nothing new, as we see in the book of Acts. Yet it wasn’t too long ago that these disagreements seldom became public. As we struggle to face challenging issues, living in the realization that belief in Christ doesn’t mean we will always agree, we must develop strategies and provide healthy environments to help us face our conflicts in a manner that gives evidence to our theology of perfect love. If we do not, we serve to illustrate its failures.

Social media offers a platform for conflict to escalate, and for millions to know what in the past was known by only a few. Many are watching to see if holiness believers can face important issues and disagreements with integrity, and demonstrate our ethic of perfect love as we listen to one another, and worship God with our minds—learning from those whose ideas stretch us and make us uncomfortable.

Most importantly, the world—and the next generation—is watching to see if we can agree to disagree and still remain in loving Christian fellowship.

Disagreements among those who claim “holiness” has been a part of our tradition since the time of our denominational founding, the time of Wesley, the time of the early church. Yet learning to handle conflicts offers us an opportunity to prove true our theology of perfect love.

Mike Schutz is senior pastor of Avon Grove Church of the Nazarene in West Grove, Pennsylvania.

Please note: All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at the time of original publication but may have since changed.