Catholics and Nazarenes: Friends or Foes?

We want to acknowledge that Catholicism takes on various characteristics in different contexts. Regionally, it may be true that Roman Catholics in your area are not open to conversation or shared mission with non-Catholics. However, this need not stop us from trying, or at least avoiding speaking ill of them. If nothing else, it should spur us onward to the same prayer that Jesus prayed: that those who believe in His name be “one.”

I met Spencer, my elementary school best friend, in kindergarten. Over the years, we did what best friends do together: had sleep-overs, got in trouble, figured out homework, and learned through each other about music, sports, and the world in general. We even went to church together. I invited him to Sunday school, worship, and summer camps. I remember that while I was excited that my best friend came to camp with me, I was all the more concerned that he come to faith in Jesus Christ. I saw it as my job to bring him to saving faith. Who else would tell him? After all, he was Roman Catholic, and they don’t know really Jesus, right?

Since then, I have learned not to assume that someone who is Roman Catholic does not know who Jesus Christ is, even to the depths of Lord and Savior. Who can blame a child for making judgments according to his own upbringing and experience? But further experience in the world, in the church, in my education, but mostly in rubbing shoulders with Roman Catholics has demonstrated to me that such overgeneralizations are not only untrue, but a hindrance to being Christ’s people together in the world.

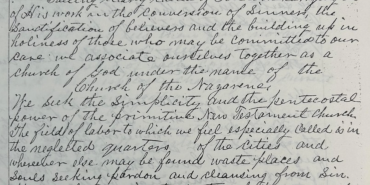

The Church of the Nazarene’s Manual provides a good foundation to understanding ourselves in relationship to other parts of the Body of Christ (“The Church”). We distinguish between the universal church (“The General Church”), various expressions of the church (“The Churches Severally”), and then ourselves (“The Church of the Nazarene”). Each is a subset of the previous. It is truly unfortunate that we must distinguish between one group and another because, in the kingdom of heaven, there is and will be no division whatsoever. When we read the heart of Jesus’ prayer in John 17: “that they will be one,” we weep.

But the fact is that we do find ourselves divided. And there are differences between us. So can we yet be “one” in ways other than strict doctrinal adherence? Might we be one in worship, in sacrament, and in mission? Can we work together compassionately and tell people that Jesus is Lord?

Not uniformity, unity in love

Let’s step back for a few moments. Indeed there are huge doctrinal, liturgical, organizational, and missional differences between the Roman Catholic Church and the Church of the Nazarene. We have a vastly different understanding of church leadership and authority, particularly concerning how the priestly function is carried out. We believe in a certain autonomy of the local congregation. Our space for and gathering of worship is highly contextualized. We value the example of Mary, but not nearly in the same ways that Roman Catholics do. We may have great appreciation for aesthetics and beauty, but the call of our founder to “make every board plain” still rings in our ears. The differences between us are factual and real.

But—

Our obvious differences need not lead us to the conclusion that we have no shared heritage or nothing to gain from learning about and associating with each other. The temptation is to assume that because we believe someone to be wrong about one thing, then they are wrong about everything. Or we somehow conclude that when someone does one thing incorrectly, then all else that they perform is also suspect.

Probably most common, we simply fear the other because we do not understand what they do and why they do it.

We must resist these temptations! Otherwise, we will find ourselves in utter isolation.

We find ourselves in a judgmental place when we use the labels on a designated church to determine whether those who are a part of that local church are true Christians or not. Most often, we fall into this temptation based on wordy doctrine rather than those things with which the Bible tells us to judge, namely: fruit.

Jesus himself demonstrated to us that what was most important were those things that people did as a result of their faith that make us truly His or not. Labels didn’t seem to be all that important to Jesus. Rather, when He says such things as, “Everybody who hears these words of mine and puts them into practice” or “Each tree is known by its fruit,” Jesus shows us that the living faith-full outflow of one’s life is truly that which He is concerned about. That second statement (about fruit) is in Luke’s version of Jesus’ most influential sermon in a section—Luke 6:37-49—that is particularly pointed toward those who would judge without thinking.

The gospel calls us not to uniformity, but to unity in love. Christ explicitly told us that people will know that we are following Him by the way they see us love each other. Paul calls us to this same mind of Christ—that we agree together in love in Philippians 2. This is the goal: loving with the love of Christ. The rest is indeed detail.

A fourth generation offshoot

It’s notable that some of our closest spiritual ancestors who were instrumental in the path to the Church of the Nazarene’s formation were not initially trying to start a new group of believers. Rather, people like Martin Luther, John Wesley, Phineas Bresee, and Jesus himself sought to be faithful right in the context in which they found themselves.

While it could be said that each of these founded a new group or denomination, their attempt was initially to call the people of whom they were a part to remember what it is to be faithful to God. Luther was Catholic. Wesley was Anglican. Jesus was a Jew.

It’s good to remember how we got here. The Church of the Nazarene and most all Protestant denominations are offshoots of the Roman Catholic Church. Succinctly, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the Church of the Nazarene was formed by a number of Wesleyan-holiness groups, many of which can be traced to the Methodist Episcopal Church. John Wesley and the earliest Methodists who lived in the 18th century were Anglican (the Church of England). The Church of England split from the Roman Catholic Church in the 1500s, shaped in part by some of the efforts of the 16th century Protestant Reformation.

In general, we can say that the Church of the Nazarene is a fourth generation offshoot of the Roman Catholic Church. This history is rather short (500 years, give or take) compared to the first 1,500 years or so that the Western Roman Church existed. The ultimate truth is that the Church of the Nazarene wouldn’t exist without the initiation of the church by Jesus Christ. But it is also true that the Church of the Nazarene wouldn’t exist without the faithfulness of the Roman Catholic Church over those 1,500 years.

We might think about it in terms of a family photo album. If the last 120 years that have passed since Bresee and Widney began the Church of the Nazarene in Los Angeles are the most recent dozen pages, then there are hundreds of pages before that, filled with the stories and pictures of faithful followers of Christ, all of whom have formed and shaped the church since Jesus ascended.

Praying for those unlike us

Over the last several years, the Lord has made it apparent to me that my attitude about other Christians needed to change and that it had to begin with prayer. As I look back now, I’m embarrassed to see that I knew things any other way. Whatever happened 400-500 years ago with the Protestant Reformation, it seems certain that what the reformers wanted more than anything was for the Roman Church to change (to be reformed!). Otherwise, it might have been called the Protestant “Secession.”

Yet half a millennium has passed. Protestants (and other groups that have grafted in and out) have done no better, splintering even more, sometimes almost to a dust. None of us who are alive today were there during the Reformation. Further, the details at the center of why much of the fight ensued are long past us. It’s very hard to imagine that Protestants and Catholics will ever be completely united this side of Christ’s return.

But isn’t this exactly what we should be praying? We could sit around pointing out to ourselves and anyone else who is listening just how stark our differences with the Roman Catholic Church are. (And it is true that when injustice or sin is as blatant as it has sometimes been, we have a responsibility to exercise a prophetic voice against sin, particularly in the church.)

But Jesus calls us in John 17 and other places to more than finger-pointing. Jesus calls us to pray for our enemies and demonstrates to us the example of inviting those unlike us to the table.

When the Roman Catholic Church was undergoing the selection of a new pope a few years ago, our church sent flowers to the Catholic churches and abbey in town with a simple note: “We’re praying for you in these days.” We received warm and grateful responses. If nothing else, the Roman Catholics in our neighborhood know that at the Church of the Nazarene in this town, they can find friends and people who love Jesus above and beyond people who will judge them for differences in doctrine and liturgical practice.

Jeremy Scott is pastor of North Street Community Church of the Nazarene in Hingham, Massachusetts.

Please note: All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at the time of original publication but may have since changed.