The Reformation(s) of the Church

Reformation before Luther

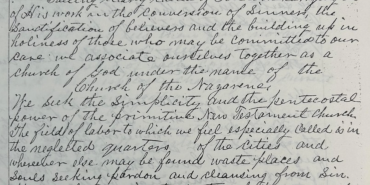

Though the catalyst to the series of events known today as the Protestant Reformation was sparked in 1517 by Martin Luther’s posting of his 95 theses to the church doors at Wittenburg, the Church had long before been engaged in the process of reformation. In fact, one could argue that ever since the fall of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden, God has been reforming. The Church continues its process of reformation today.

The Prophets of the Old Testament were constantly reminding the people of God that God was patiently seeking to reform them.

The coming of Jesus and the new Kingdom He embodied was a clarification of the reform that God had been attempting throughout the Old Testament. Even after the resurrection of Jesus, the disciples felt the need for ongoing reform. The experience of Pentecost in Acts 2 assisted the Church in carrying out the admonition of Jesus (Matthew 28) to “go into all the world,” because the Kingdom of God defies societal limitations and borders.

The work of God among the Gentiles through the ministries of Peter and Paul added another dimension of reform, culminating in key agreements among early church leaders in Acts 15. Through the words of Paul and other writers, the rest of the New Testament demonstrates a variety of “mini-reforms” needed among a growing and changing constituency. God lovingly and consistently reforms the Church.

The “next generation” believers, commonly referred to as the Church Fathers and Mothers, experienced a myriad of reformation opportunities, the best known of which were the Ecumenical Councils and the formulation of creeds in the first eight centuries of the Church’s history. These steps toward reformation led to unity among several groups, but also resulted in schisms. Most notably, the Eastern and Western branches of the Church (the Orthodox and the Roman Catholic groups, respectively) experienced an official schism in 1054 A.D.

On Luther’s Doorstep and Beyond

Reformation has always been a part of the Church’s conversation about itself.

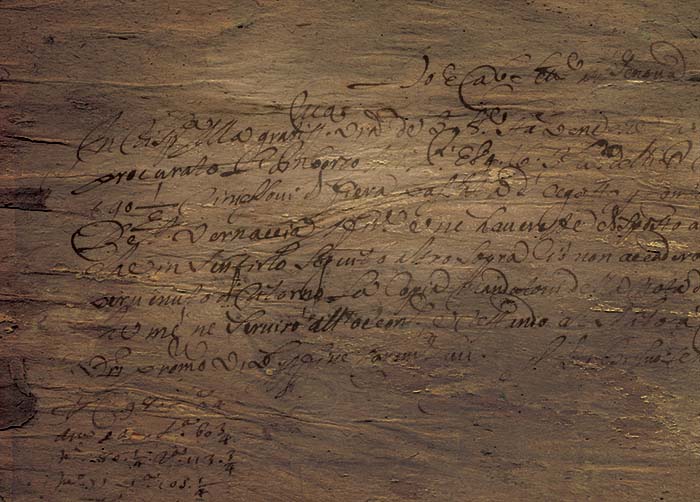

Around the time of Martin Luther, the stage had been set for a particularly earth-shaking renewal. A century before Luther, for example, a Czech priest and professor named Jan Hus (1369-1415) had been put to death for writings and protests regarding the actions of key church leaders. In fact, after Luther posted his 95 theses, many began referring to Luther as a “modern Huss-ite.” Many factors surrounding Luther’s contribution to reformation in the early sixteenth century, such as his education, the invention of Gutenburg’s printing press, and Luther’s powerful friends, allowed Luther’s message to transcend the confines of his village and of Germany and become a key catalyst of reforms already taking place throughout the world. From there came other movements: Calvinists, Arminians, Anabaptists, Quakers, Puritans, and Wesleyans, just to name a few.

Charles W. Christian is Managing Editor for Holiness Today

Holiness Today, September/October 2017

Please note: This article was originally published in 2017. All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at that time but may have since changed.