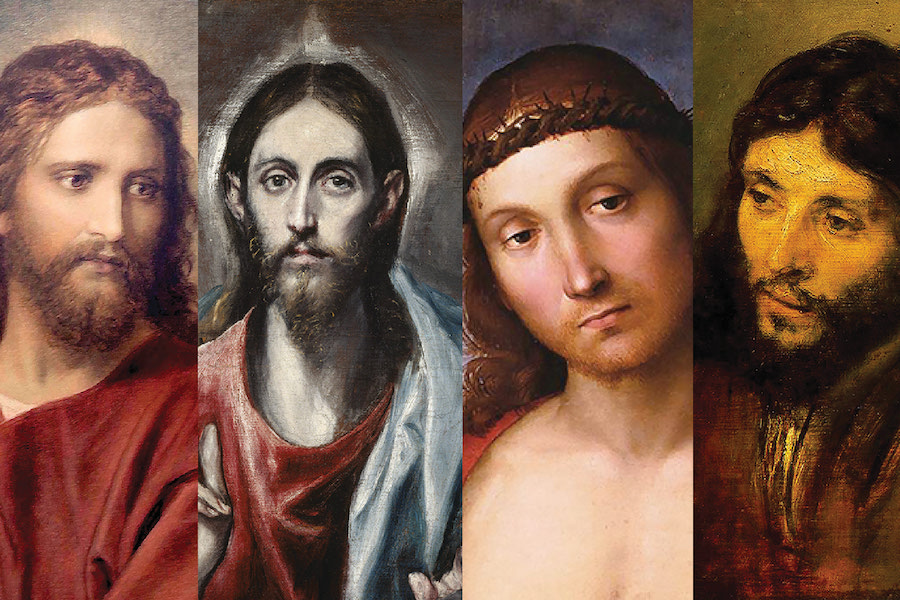

One Jesus Painted by Four Artists

The term “Gospel” (euangelion in Greek) means “good news,” and the Gospels tell the story of the good news of Jesus’ life. In the church, we speak quite rightly about Jesus’ life as a unified narrative. In the Advent and Christmas seasons, preaching interweaves stories about Jesus’ birth as recorded in the early chapters of Matthew’s Gospel and Luke’s Gospel. Our manger scenes include both shepherds (from Luke 2:8-20) and wise men (from Matthew 2:1-12) even though no Gospel coordinates the visits of both groups of unlikely worshippers.

Good Friday and Easter services mix and match episodes, recounted in different ways across the four Gospels. For example, no matter which Gospel we happen to be reading, many of us take it as common knowledge that Peter was the disciple wielding the sword at Jesus’ arrest (John 18:10-11) and that Jesus healed the man’s ear (Luke 22:50) even though only one Gospel provides us each piece of information.

Christmas and Easter stories are only the tip of the iceberg: Why do we have four Gospels, and why are there such differences between them?

The Four Gospels in the Early Church

Churches have a long tradition of “harmonizing” (blending together) Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John. This practice goes back to ancient times. In the second century (ca. 170 ad), a well-educated Christian named Tatian attempted a blended Gospel that came to be called the Diatessaron (which means, “through the four”). It seems Tatian’s goal was to reduce the apparent conflicts between the already popular but not yet officially canonized four Gospels and to provide churches with one coherent account of Jesus’ birth, ministry, death, and resurrection. Tatian’s single, harmonized Gospel gained traction for a time and in certain regions.

Yet Tatian’s approach did not triumph. Another gifted Christian thinker, Irenaeus of Lyons (ca. AD 130-202), was one of the loudest voices insisting on the necessity of the four Gospels. His arguments in support of the four separate Gospels were just a piece of his larger project, Against Heresies (ca. AD 180), in which he countered heretical teaching that attributed the created world to a lesser god and denied the humanity of Jesus. Addressing those clamoring for more Gospels (particularly more transcendental or “gnostic” approaches to Jesus) or for only one, Irenaeus argues that there cannot be more or fewer than four (Against Heresies III.11.8).

During Irenaeus’s time, our current four Gospels were beginning to be seen as Scripture and were being read in church gatherings and circulated as a set. Irenaeus reinforces that what makes these books uniquely valid is their close connection to the Spirit-filled apostles of the Risen Lord. Irenaeus identifies Matthew and John as disciples of Jesus while naming Mark as Peter’s interpreter and Luke as a companion of Paul (III.1.1).

Further, Irenaeus draws attention to the image of the living creatures surrounding the throne in the Revelator’s vision of God’s throne room (Rev. 4:6-8). The angelic creatures, each with different faces—lion, ox, human, and eagle—give unceasing praise to the One seated on the throne.

Irenaeus makes the connection: the four Gospels are like these four creatures.

They are unmistakably different and yet point faithfully to the same reality: Jesus.

Unique Contributions of the Four

Richard Burridge likens the Gospel authors to artists, each painting a portrait of Jesus with his own unique brush strokes and interests in focus.1 Historically, these Gospels are more than just the products of isolated biographers. There was certainly community involvement in preserving and retelling the stories of Jesus. The Church’s traditional naming of the Gospels does not give “possession” to each author but instead suggests that the unified good news is told in the key of or “according to” each Gospel author.

In the Gospel According to Matthew, Jesus’ Jewish lineage and fulfillment of Scripture shines forth. Jesus’ birth is described mostly from the perspective of God’s dealings with Joseph. Jesus is a teacher who eclipses the Mosaic model of law-giver (see the Sermon on the Mount in Matt. 5-7). Jesus’ interpretation of the law is authoritative, which leads Him into conflict with fellow Jews who also take the Jewish law seriously (12:12). Matthew presents Jesus’ future perspective, both for the church (18) and its leaders (16:17-19). Finally, some of Matthew’s unique parables insist on the righteous judgment of God (25:31-46), while others depict God’s excessive grace (20:1-16).

In the Gospel According to Mark, the question of Jesus’ identity and origin dominates the narrative (see Mark 1:24; 2:7; 3:21-22; 4:41; 6:3; 8:27-30; 14:61). Mark portrays Jesus as enigmatic; even those closest to Him fail to grasp who He truly is (e.g., 8:17-21).

Mark portrays Jesus as enigmatic; even those closest to Him fail to grasp who He truly is.

In the end, the desolation of Jesus’ crucifixion culminates in the tearing of the temple curtain (15:38; perhaps a sign of the Father’s mourning over a “beloved son,” cf. 1:11; 9:7). Our earliest copies of Mark end at 16:8, which means that the Gospel probably left untold the stories of faithful witnesses to the resurrected Jesus. It remained for hearers to take up and share that “good news” with which the book began (1:1).

The Gospel According to Luke provides us with two of the most beloved parables of Jesus (Luke 10:25-37; 15:11-32) and presents Jesus’ birth story from the perspective of God’s interactions with Mary. Both Zechariah and Mary lift up profoundly theological words of praise to the God of Israel who is both bringing fulfillment and a new thing to God’s people (1:46-55, 67-79). Luke paints Jesus’ preaching and teaching in light of an overturning of expectations: His coming reverses the fortunes of many (2:24-35; 18:9-14). In Luke, we have a lengthy account of Jesus’ post-resurrection teaching, in which He explains how Old Testament Scriptures point to Him as the Messiah on the Road to Emmaus (24:13-35).

A cosmic view of Jesus’ identity launches the Gospel According to John: “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God” (1:1). This Gospel is a study in contrast, in light versus dark, in which some people that should understand Jesus fail to do so (e.g., 3:10), and those who seem like outsiders come to recognize Jesus as Messiah (e.g., 4:29). John’s Gospel contains unique stories, like the healing of the paralyzed man (5:1-15), the man born blind (9), and the raising of Jesus’ dear friend Lazarus (11:1-44). The Gospel draws on the perspective and testimony of “the beloved disciple” (see 21:24), whose stated purpose in compiling these particular stories is to inspire belief (20:30-31).

A Unifying Message

Despite the differences noted above, there are remarkable similarities between the Gospels.

Crucial for understanding Jesus’ ministry is John the Baptist’s ministry that precedes it, as its prominence in all four Gospels signifies (Matt 3:1-17; Mark 1:1-11; Luke 3:1-22; John 1:6-8, 15-34). Jesus spends His ministry pouring out restoration and truth; He teaches and heals throughout all four Gospels. Yet, only the miracle of the feeding of the 5,000 is repeated in a recognizable fashion across all four (Matt 14:13-21; Mark 6:30-44; Luke 9:10-17; John 6:1-15).

For example, in each Gospel, Jesus raises at least one dead person back to life, but the person and his or her story varies (e.g., Jairus’s daughter in Mark 5:35-43; a widow’s son in Luke 7:11-17). In all four, Jesus cannot escape the antagonism of His fellow Jews and ultimately a conflict that leads Him into the powerful hands of the ruling Roman empire (e.g., Matt 27:11-27). Each Gospel tells of Jesus’ death and, although the details can vary (cf. Mark 15:21 and John 19:17), His fidelity to the Father withstands His suffering.

In each Gospel account, Jesus’ body does not languish in the tomb but is raised up in the early morning of the third day (e.g., Luke 24:1). Women undoubtedly encounter the empty tomb and the Risen Jesus first, but the way this happens is told differently (Matt 28:1-10; Mark 16:1-8; Luke 24:1-11; John 20:1-2, 11-18). The progression of Jesus’ “portrait,” so to speak, is the same, but the colors, brush strokes, and surrounding scenery change from Gospel to Gospel.

Reality and Theology of the Four Gospels

The truth of the four Gospels is at once beautiful and unsettling. The Spirit has inspired and the Church has recognized four different accounts of Jesus’ story. In these four narratives, the Gospel writers highlight different dimensions and perspectives of Jesus, like the facets of a gemstone glinting in the light. At the same time, this plurality of perspectives is in opposition with the very human urge to have one neat and tidy framework in which we can understand Jesus.

Human life is much like that. We carry with us the perspectives shaped by our upbringings, our families, our native tongues, our wealth or poverty, our political leanings, our educations, etc. The intersection of personal and social identities might divide us. In fact, sometimes these differences make communication difficult. Yet, in Christ’s Church, these differences cannot remain a barrier but must become beautiful contributions to the body (see 1 Cor. 12 or Eph. 2:11-22). The four Gospels symbolize what is true of the body of Christ in the Church; only in our many differences, unified by one Spirit, is the wholeness of Christ represented.

As Irenaeus suggested long ago, Jesus is not the sort of Savior who can be captured in one image.

A singular portrait cannot do our Risen Lord justice. So, we have four. We do not have four different saviors as if John’s Jesus were irreconcilable with Mark’s. Instead, we have four glimpses of our Emmanuel, God With Us. Only when reading with respect for the Gospels’ differences, while leaning into their unity, can we encounter the one Jesus to which each Gospel points. While the Gospels help us better understand who Jesus is, He is not contained in these ancient, faithful books. He is risen, reigning at the right hand of the Father.

Kara J. Lyons-Pardue is associate professor of New Testament at Point Loma Nazarene University.

1. Burridge, Richard. Four Gospels, One Jesus?: A Symbolic Reading, Second Edition. Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2005.

Please note: All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at the time of original publication but may have since changed.