The English Reformation

It may seem a stretch to try to connect the sixteenth century English Reformation with the Wesleyan movement, but given John Wesley’s ministry as a priest within the Church of England and his vital role in the formation of the Wesleyan movement, the connection is stronger than some might think. The revival that swept up figures like John and Charles Wesley in the eighteenth century or even later Wesleyan figures like Francis Asbury, Phoebe Palmer, and H. Orton Wiley was distinctly connected to the patterns and the theology of Anglicanism, many of those patterns and the theology behind them formed in the English Reformation.

A Long Process of Reformation

The English Reformation, among the various local reformations that took place in Germany, Switzerland, Italy and elsewhere, is likely the most complex of the reform movements and the longest in duration. Arguably the English reforms began under Henry VIII in the 1530s and extended to the last attempt by a Catholic to take the throne of England in 1745. However, it is also possible to look at the reform under the reigns of Henry, his son, Edward, and his two daughters, Mary and Elizabeth. Each of them is unique in emphasis and thus in outcome.

While most assume that the English Reformation was launched because Henry VIII wanted a divorce, that narrative is too simplistic. Henry was very concerned to have a male heir and was convinced that he could not do so with Katherine of Aragon. However, the “King’s great matter,” as it was called, was not the launching point of the Reform but rather the straw that broke the camel’s back. England, like many countries north of the Alps, had been slowly but surely chipping away at the pope’s authority for centuries and so in many ways what Henry did was to deny papal authority over the Church in England and in the process created the Church of England, detached from Rome but almost completely the same in many other ways.

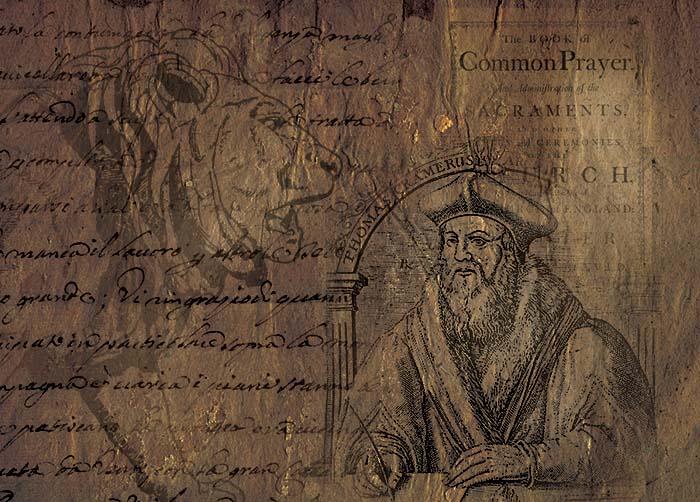

Unlike continental European reform movements, the English reforms were distinctly top-down and had the full force of government behind them. And during the reign of Edward VI, Henry’s son, the reforms took a distinctly Protestant turn. It was under Edward that Thomas Cranmer, Archbishop of Canterbury, released his famous work, The Book of Common Prayer, in 1549. This reform changed the worship of England. For the first time, the worship services would now be in English.

Henry had dissolved the monasteries and convents of England who for over 1000 years had been centers of prayer for the nation. With Cranmer’s Prayer Book, this void was partially filled because the churches were to hold Morning and Evening Prayer to mark the day much like the monks had done previously. Arguably, Cranmer was trying to create a nation whose daily patterns were marked by prayer, the reading of scripture, and the keeping of liturgical seasons.

Thomas Cranmer and the Book of Common Prayer

The importance of Cranmer’s Prayer Book is hard to overstate since his words became the pattern by which English-speaking people throughout the world would pray for centuries. Most Anglican churches, as well as many other Protestant churches, still pray using his words.

But Edward did not live long and Mary came to the throne in 1552. Mary was not a Protestant and returned England to the Catholic fold. She is known today by the nickname “Bloody Mary,” a term from Protestant propaganda that is not fair to her or her reign. Foxe’s Book of Martyrs created the picture of Mary the tyrant against pious Protestants, men, women, and even children. It should be noted that she was the first woman to rule England and as a queen, she was very successful. It was Mary who launched what would eventually become the Royal Navy.

Yet when Mary died childless, her half-sister, Elizabeth (now known as Elizabeth I, 1533-1603) came to the throne and restored most of the reforms of her father and brother. She reinstituted the Book of Common Prayer and denied papal authority over the Church of England. She is credited with what is called the “Elizabethan Settlement,” a moderating approach that brought together within the Church of England both Catholic and Protestant interests. In other words, the Church had the ceremonial, sacraments, and hierarchy of Catholicism combined with a more Protestant approach to the Scriptures and justification as something that comes by faith. This has been called a via media, or, middle way, but it should be seen more as a comprehensive approach that encompassed competing interests rather than staked a claim between them.

The Legacy of the English Reformation

So, how does Wesley relate to all of this? First, he lived and died in the Church of England. His parents, Samuel and Susanna, raised Wesley and his siblings according to the faith of the Church of England. Wesley was a priest in the Church of England, and despite his innovations (which later emerged as a separate Methodism), he never left her. He was shaped and formed by her theology, her approach, and her liturgy. In fact, one could say that if you know the King James Bible and the Book of Common Prayer, you know the greatest influences of Wesley’s theology. One way that this is easily seen is in Wesley’s understanding of grace, a theme that became vitally essential to Wesleyanism. Wesley defined grace simply as “the power of the Holy Spirit.” And, he came to that conclusion from the Prayer Book.

In the service of Morning Prayer there is a prayer called The Collect for Grace. It never once uses the word “grace,” but uses synonyms instead. Grace is described as God’s governance, His “mighty power” and His empowerment of believers. The prayer asks that by God’s “governance,” the believer might “fall into no sin, neither run into any kind of danger,” but that everything we do might be “righteous” in God’s sight.

This empowerment and the holiness that is its outcome would become a hallmark of Wesleyanism and a driving force behind both early Methodism and the Holiness Movement.

Secondly, Wesley embraced the both/and approach of Anglicanism. He combined a Catholic view of holiness – especially the belief that it is attainable in this life – with a Protestant view of justification by faith. In fact, Wesley would argue that both justification (what God does for us) and sanctification (what God does in us) are gifts, and the only requirement on our part is faith. The Wesleyan movement owes much to Anglicanism for its approach to theology: a “practical divinity” committed to a holistic approach to the Christian life.

Lastly, Wesley learned not only about “heart religion” from his English heritage and the help of a few German pietists, but also about the need for what he called “constant communion.”

He believed that the same God who changes our hearts also meets us in Holy Communion.

God is there, he would argue, and those who come to the Table will meet Him there.

As Wesleyans, we have much to be thankful for from those who launched the Reformation in England. It is a rich heritage worth exploring. But most of all, we can be thankful for the opportunity to be in relationship with the God who can “cleanse the thoughts of our hearts” so that perfect love might become the reigning attribute of our lives.

Ryan N. Danker is Assistant Professor of the History of Christianity and Methodist Studies, Wesley Theological Seminary, Washington, D.C.

Holiness Today, September/October 2017

Please note: This article was originally published in 2017. All facts, figures, and titles were accurate to the best of our knowledge at that time but may have since changed.